Unraveling "Does It Hurt?": A Deep Dive Into Pain's Complexities

The question, "Does it hurt?", is deceptively simple, yet it unlocks a vast and intricate world of human experience. From the sharp sting of a paper cut to the dull ache of chronic illness, or even the profound sorrow of a broken heart, pain manifests in countless forms. This article delves deep into the multifaceted nature of pain, exploring its biological underpinnings, psychological dimensions, and the profound impact it has on our lives.

We often ask this question out of empathy, curiosity, or concern, seeking to understand another's discomfort or to anticipate our own. But beyond the immediate sensation, understanding "does it hurt?" requires a journey into neuroscience, psychology, and the deeply personal realm of individual perception. It’s a query that transcends mere physical sensation, touching upon emotional states, memory, and even our cultural understanding of suffering.

The Simple Question, The Complex Answer

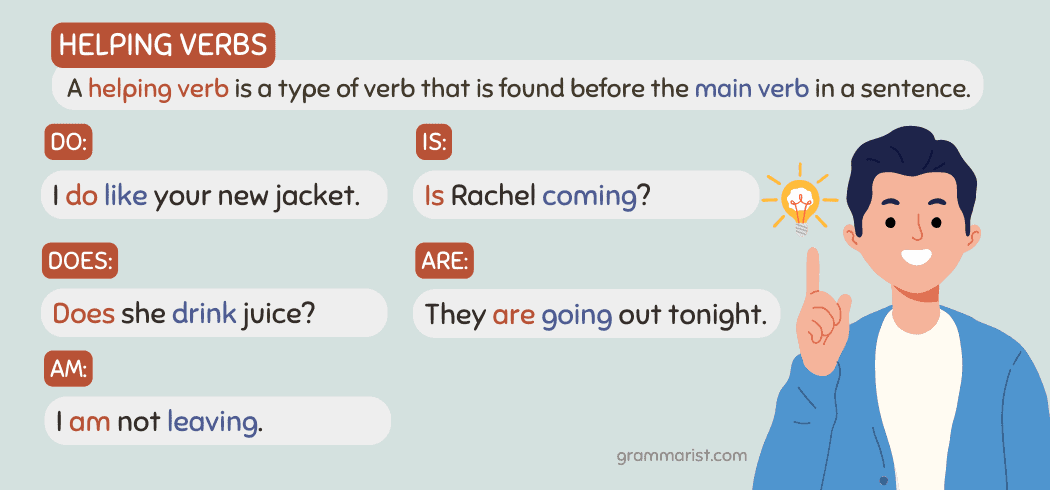

At its core, the phrase "Does it hurt?" is a grammatically straightforward query. Understanding when to use "do" and "does" is key for speaking and writing English correctly. Both "do" and "does" are present tense forms of the verb "do." The correct form to use depends on the subject of your sentence. For example, you use "do" with the pronouns "I," "you," "we," and "they" (e.g., "Do you know the answer?"). However, "does" is the third-person singular in the present tense of "do," used specifically with "he," "she," and "it." Thus, when referring to an inanimate object or a singular, unspecified entity, "Does it hurt?" is the grammatically correct formulation. This present simple of "do," used with "he/she/it," forms the basis of countless everyday questions.

Yet, despite its grammatical simplicity, the actual meaning and implications of "does it hurt?" are profoundly complex. This question isn't merely about linguistic rules; it's about sensation, experience, and the deeply subjective reality of pain. When someone asks, "Does it hurt?", they are probing the depths of another's physical or emotional state, seeking to understand a sensation that is inherently personal and often difficult to articulate. The answer can range from a simple "yes" or "no" to a detailed description of agony, a stoic denial, or even a profound silence. The complexity lies in the fact that pain is not just a straightforward physiological response; it's a dynamic interplay of biological signals, psychological factors, and environmental influences, making the answer to "does it hurt?" far more nuanced than a simple dictionary definition of the verb "does" might suggest.

Understanding the Physiology of Pain

To truly grasp "does it hurt?", we must first delve into the intricate biological mechanisms that underpin the experience of pain. Pain is fundamentally a protective mechanism, an alarm system designed to alert us to potential or actual tissue damage. This complex process begins at specialized nerve endings called nociceptors, which are found throughout the body in the skin, muscles, joints, and internal organs. These nociceptors are specifically tuned to detect noxious stimuli—things like extreme temperatures, intense pressure, or irritating chemicals released during injury.

When a harmful stimulus triggers these nociceptors, they convert the energy of the stimulus into electrical signals. These signals then travel along sensory nerves, up the spinal cord, and eventually reach various areas of the brain. Key brain regions involved in processing pain include the thalamus (which acts as a relay station), the somatosensory cortex (which identifies the location and intensity of the pain), the limbic system (involved in the emotional response to pain), and the prefrontal cortex (involved in cognitive aspects like planning and decision-making related to pain). The brain then interprets these signals, creating the conscious perception of pain. This intricate pathway ensures that when something truly threatens our well-being, our body sends a clear, undeniable message: "Does it hurt? Yes, and you need to pay attention!"

Nociceptive Pain: The Body's Alarm System

Nociceptive pain is the most common type of pain, resulting from actual or potential tissue damage. It’s the body’s immediate and direct response to injury. This category can be further divided into two main types:

- Somatic Pain: Originates from the skin, muscles, bones, joints, and connective tissues. It's typically well-localized, meaning you can point to exactly where it hurts. Examples include the sharp pain of a cut, the throbbing of a sprained ankle, the ache of a broken bone, or the soreness after intense exercise. This type of pain often responds well to common pain relievers.

- Visceral Pain: Arises from internal organs within the body, such as the stomach, intestines, bladder, or heart. Unlike somatic pain, visceral pain is often diffuse, poorly localized, and can be referred to other areas of the body. For instance, heart attack pain might be felt in the arm or jaw. It can manifest as a deep ache, pressure, or cramping sensation. Examples include the pain of appendicitis, gallstones, or menstrual cramps.

Nociceptive pain, whether somatic or visceral, serves as a crucial warning signal, prompting us to withdraw from harm or protect an injured area, thereby preventing further damage. It’s the body’s way of ensuring survival and recovery.

Neuropathic Pain: When Nerves Misbehave

While nociceptive pain is a response to tissue damage, neuropathic pain is fundamentally different. It arises from damage or dysfunction of the nervous system itself, rather than from stimulation of nociceptors. This type of pain is often described as burning, shooting, stabbing, tingling, or electric shock-like. It can occur spontaneously, without any apparent stimulus, or be triggered by very light touch (allodynia) or exaggerated responses to painful stimuli (hyperalgesia).

Common causes of neuropathic pain include:

- Diabetes: Leading to diabetic neuropathy, often affecting the feet and hands.

- Shingles (Postherpetic Neuralgia): Persistent pain after a shingles outbreak.

- Spinal Cord Injury: Damage to the spinal cord can disrupt nerve signals, leading to chronic pain.

- Stroke: Central post-stroke pain can occur due to damage in brain areas involved in pain processing.

- Nerve Compression: Conditions like sciatica (compression of the sciatic nerve) or carpal tunnel syndrome.

- Chemotherapy-induced Neuropathy: Nerve damage caused by certain cancer treatments.

Neuropathic pain is often chronic and can be particularly challenging to treat, as it doesn't respond as predictably to conventional pain medications. It represents a situation where the "does it hurt?" answer is a resounding "yes," but the underlying mechanism is a malfunctioning alarm system, sending pain signals even when there's no ongoing tissue threat.

The Psychology of Pain: More Than Just Physical Sensation

While the physiological pathways of pain are well-documented, the experience of pain is profoundly subjective and influenced by a myriad of psychological factors. This is where the simple question, "Does it hurt?", becomes truly complex. Two individuals with the exact same injury might report vastly different levels of pain, illustrating that pain is not merely a direct output of tissue damage but a complex perception shaped by the brain.

Several psychological elements play a crucial role:

- Mood and Emotion: Anxiety, depression, and stress can significantly amplify pain perception. Conversely, positive emotions or a relaxed state can reduce it. Someone feeling anxious about a procedure might report that "does it hurt?" more intensely than someone calm and prepared.

- Attention and Distraction: Focusing on pain tends to increase its intensity, while distraction can diminish it. Think of how a child might forget a scraped knee while engrossed in play, only to remember it later.

- Expectations and Beliefs: What we expect about pain can powerfully influence how we experience it. The placebo effect (pain reduction due to belief in a treatment, even if it's inert) and the nocebo effect (increased pain due to negative expectations) are prime examples. If you expect a shot to hurt, it often feels worse.

- Past Experiences: Previous painful experiences can condition our response to future pain. A history of severe pain might lead to heightened sensitivity or fear of recurrence.

- Coping Strategies: Active coping mechanisms, such as problem-solving or seeking support, can help manage pain, while passive coping, like catastrophizing (dwelling on and exaggerating pain), can worsen it.

Chronic pain, in particular, often becomes intertwined with psychological distress, leading to a vicious cycle where pain exacerbates anxiety or depression, which in turn amplifies the pain. Understanding these psychological dimensions is critical for effective pain management, as addressing the mind is often as important as treating the body when someone answers "yes" to "does it hurt?".

Emotional Pain: When the Heart Aches

The question "Does it hurt?" isn't confined to the realm of physical sensation. Humans are capable of experiencing profound emotional pain, which, though lacking a tangible physical injury, can feel just as real, if not more debilitating, than physical discomfort. Emotional pain encompasses a wide spectrum of feelings, from grief and heartbreak to betrayal, rejection, loneliness, and profound sadness.

Remarkably, neuroscience research has shown that emotional pain activates some of the same brain regions as physical pain, particularly areas like the anterior cingulate cortex and the insula. This overlap suggests that the brain processes both types of pain through similar neural pathways, lending credence to the idea that a "broken heart" isn't just a metaphor. The ache of loss, the sting of betrayal, or the gnawing emptiness of loneliness can manifest with symptoms akin to physical discomfort, such as a tight chest, stomach upset, or a general feeling of malaise.

Examples of emotional pain include:

- Grief: The intense sorrow and anguish following the loss of a loved one.

- Heartbreak: The deep emotional distress caused by the end of a romantic relationship.

- Betrayal: The profound hurt and disillusionment when trust is broken by someone close.

- Rejection: The painful feeling of being excluded or unwanted, whether in social, professional, or personal contexts.

- Loneliness: The distressing feeling of being isolated or lacking meaningful connection.

Just like physical pain, emotional pain serves a purpose. It signals that something important is amiss in our social or emotional world, prompting us to seek connection, process loss, or adjust our behaviors. While there are no bandages or painkillers for a broken spirit, acknowledging and validating emotional pain is the first step toward healing. When someone asks "Does it hurt?" after a significant loss, the answer is often a resounding "yes," signifying a wound that requires compassion, understanding, and time to mend.

The Role of Context and Perception

The answer to "does it hurt?" is never given in a vacuum. The context in which pain occurs, as well as an individual's unique perceptual filters, profoundly shape the experience. What might be excruciating for one person could be merely uncomfortable for another, even with similar stimuli. This variability highlights the deeply personal nature of pain.

Consider the following contextual and perceptual influences:

- Cultural Background: Different cultures have varying norms for expressing and perceiving pain. Some cultures encourage stoicism, while others allow for more overt expressions of discomfort. These cultural scripts can influence how individuals report "does it hurt?" and how others interpret their pain.

- Upbringing and Learning: Our early experiences and how our caregivers responded to our pain can shape our pain coping mechanisms and thresholds. Children who are taught to "tough it out" might develop a higher pain tolerance than those whose pain was always immediately attended to.

- Meaning of the Pain: The significance attributed to the pain can alter its perception. Pain experienced during childbirth, for example, is often viewed differently than pain from an injury, as it's associated with a positive outcome. Similarly, pain endured during a marathon might be perceived as a sign of accomplishment rather than pure suffering.

- Attention and Expectations: As mentioned previously, focusing intently on pain can amplify it, while distraction can reduce it. If you're expecting a painful procedure, the anticipation alone can heighten your sensitivity.

- Social Support: The presence of empathetic friends, family, or healthcare providers can significantly buffer the pain experience. Feeling understood and supported can reduce anxiety and make pain more manageable. Conversely, feeling dismissed or isolated can exacerbate it.

- Environment: A calm, reassuring environment can help reduce pain perception, whereas a noisy, chaotic, or threatening setting can intensify it.

These factors demonstrate that pain is not a fixed, objective sensation but a dynamic, constructed experience. When we ask "does it hurt?", we are not just inquiring about a biological signal, but about a complex interplay of personal history, cultural norms, emotional states, and immediate circumstances. Understanding these layers is crucial for providing compassionate and effective care.

Managing and Coping with Pain

When the answer to "does it hurt?" is a persistent "yes," finding effective strategies for management and coping becomes paramount. Pain, especially chronic pain, can severely impact quality of life, affecting physical function, emotional well-being, and social interactions. A comprehensive approach often involves a combination of medical, psychological, and lifestyle interventions.

Medical Interventions:

- Pharmacological Treatments: Ranging from over-the-counter pain relievers (NSAIDs, acetaminophen) for mild to moderate pain, to prescription medications like opioids, muscle relaxants, or neuropathic pain medications (e.g., gabapentin, pregabalin) for more severe or specific types of pain.

- Physical Therapy: Essential for restoring function, strength, and flexibility, especially for musculoskeletal pain. Therapists use exercises, manual therapy, and modalities like heat/cold therapy.

- Interventional Procedures: Injections (e.g., nerve blocks, epidural steroids), radiofrequency ablation, or even surgical interventions for certain conditions.

Alternative and Complementary Therapies:

- Acupuncture: Involves inserting thin needles into specific points on the body to stimulate natural pain relief.

- Massage Therapy: Can alleviate muscle tension and improve circulation, reducing certain types of pain.

- Chiropractic Care: Focuses on spinal adjustments to address musculoskeletal pain.

- Herbal Remedies and Supplements: While some may offer mild relief, it's crucial to consult a healthcare provider due to potential interactions or side effects.

Psychological Strategies:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Helps individuals identify and change negative thought patterns and behaviors related to pain, improving coping skills.

- Mindfulness and Meditation: Techniques that train attention and awareness, helping individuals observe pain without judgment and reduce its emotional impact.

- Relaxation Techniques: Deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and guided imagery can reduce muscle tension and stress, which often exacerbate pain.

Lifestyle Changes and Self-Care:

- Regular Exercise: Even gentle activities like walking or swimming can release endorphins, improve mood, and strengthen the body.

- Healthy Diet: Anti-inflammatory foods may help reduce pain, while processed foods can worsen it.

- Adequate Sleep: Poor sleep can amplify pain perception; prioritizing good sleep hygiene is crucial.

- Stress Management: Engaging in hobbies, spending time in nature, or practicing self-compassion can lower stress levels.

- Building a Support System: Connecting with friends, family, or support groups can provide emotional resilience and practical help.

Effective pain management is often a journey of trial and error, requiring patience and collaboration with healthcare professionals. The goal is not always to eliminate pain entirely, but to reduce its intensity, improve function, and enhance overall quality of life, transforming the answer to "does it hurt?" from an overwhelming burden to a manageable challenge.

When to Seek Professional Help

While many minor aches and pains can be managed with self-care, there are clear instances when the answer to "does it hurt?" warrants professional medical attention. Ignoring persistent or severe pain can lead to worsening conditions, chronic issues, and a significant decline in quality of life. Knowing when to consult a doctor is crucial for proper diagnosis and effective treatment.

You should seek professional help

One Dose In, And Your Life Will Never Be The Same!

When to Use Do, Does, Am, Is & Are?

do and does worksheets with answers for grade 1, 2, 3 | Made By Teachers