Getting To Know DEM And Chron Data - Earth's Surface And Beyond

Have you ever wondered how we get those amazing 3D maps of our planet, the ones that show every hill and valley? Or, perhaps, you've heard whispers about certain charges that come up in big shipping deals, something called "dem" and "chron"? It turns out these terms, while sounding a bit technical, touch on some pretty interesting parts of how we understand our world and how business gets done. We're going to take a closer look at both, so you can get a better idea of what they mean and why they matter.

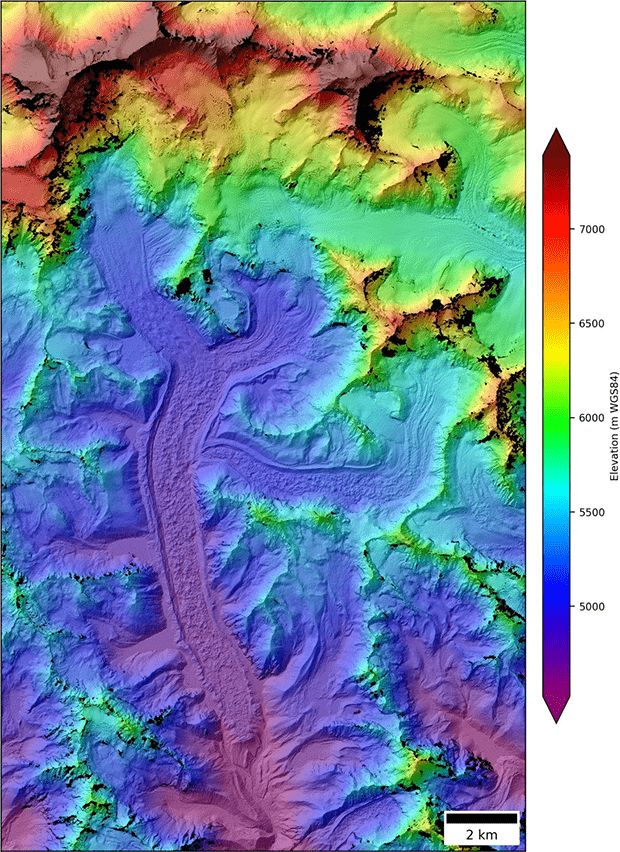

You see, when folks talk about "DEM" in one breath, they might be talking about a way to measure the ground's height, like a digital picture of the earth's surface. These pictures, or models, are put together using special tools and information from, say, satellites way up high. It's how we get to see what the land truly looks like, from the tallest peaks to the lowest valleys, all from data gathered in a pretty cool way.

Then there's the other "DEM," and its companion, "chron," which pop up in a completely different kind of conversation – the world of trade and shipping. These are, as a matter of fact, fees that can come into play when ships are loading or unloading goods. It’s like a little penalty for taking too long, and it's something that businesses keep a close eye on to make sure things run smoothly. So, it's clear these two "DEMs" and "chron" are quite different, yet both are important in their own areas.

Table of Contents

- What Are DEMs and How Are They Made?

- Where Do We Get These DEMs and Chron?

- What About the Details of DEMs and Chron?

- What About Other Meanings of DEM and Chron?

- How Do We Use DEMs and Chron?

What Are DEMs and How Are They Made?

When we talk about "DEMs" in the context of maps, we're really talking about a Digital Elevation Model. This is a kind of picture that shows us the height of the ground at different spots. You know, it's like a detailed blueprint of the land's ups and downs. These models are put together using a few different methods, each with its own special way of gathering the information. For instance, some of these models are created by taking pictures from space, like from satellites. It’s a pretty neat way to get a bird's-eye view of the entire land below, capturing all the subtle changes in height.

One common way to put these models together involves something called "stereo photography." This is, basically, like taking two pictures of the same spot from slightly different angles, just like your eyes see things. Then, a computer figures out the height differences by comparing those two pictures. It's a bit like how our brains create a sense of depth from what our two eyes see. These methods often use what we call "visible light bands," which is just the light we can see with our eyes, to get the clearest possible images of the ground. So, it's really about looking at the world from a unique perspective to build these height maps.

Different Ways to Create DEMs and Chron

When it comes to putting together these digital height models, or DEMs, there are, you know, a couple of main paths that people follow. One way, as we just talked about, involves taking pictures from space, using special sensors. These sensors are like very advanced cameras that can capture the land's shape from far away. For example, some of these models come from sensors that Japan has sent into space, like the ones used for ASTER and AW3D data. These particular pieces of equipment use that stereo photography idea, looking at the ground with visible light to figure out how high everything is.

It's interesting, really, because the AW3D data came along a bit after the ASTER data, but they both work on a similar principle. They're both trying to get a good read on the ground's height by looking at it from two slightly different angles. So, you might find that, in some respects, their basic features, like how detailed they are, are quite similar, even though one came out later than the other. This method is a pretty common way to build these digital pictures of the land, giving us a good idea of its shape. And when we think about "chron" here, it's a good reminder that these technologies develop over time, with newer versions offering different features or improvements.

Where Do We Get These DEMs and Chron?

So, where do these digital elevation models, these DEMs, actually come from? Well, a lot of them are, like, sourced from really impressive places. Some of these models are put together using pictures taken by Maxar, which is a company that specializes in satellite imagery. They have these powerful cameras up in space that capture incredibly detailed views of the Earth's surface. It's pretty amazing to think that the maps we use can come from something so far away, yet so precise.

Then there are also contributions from big organizations, like NASA. They have a program called the Commercial Smallsat Data Acquisition, or CSDA, program. This program works with smaller satellites to get even more data. And there's also the Polar Geospatial Center, or PGC, which helps gather and process this kind of information. These groups work together to make sure we have plenty of data to create these detailed models of our planet. It’s a collaborative effort, you know, bringing together different sources to build a complete picture.

Specific Examples of DEM Sources and Chron

Let's talk about some specific examples of where these DEMs come from. One very well-known source is the ASTER GDEM. The very first version of this particular model was put out in 2009. Then, a few years later, in 2011, a second version became available. These updates are, as a matter of fact, pretty common for this kind of data. The ASTER GDEM version 3, which is a more recent one, still uses the same kind of file format, called GeoTIFF, and it keeps the same way of dividing up the map into a grid and tiles. This consistency makes it easier for people to use the different versions over time.

Another really important source for these models is the Copernicus Digital Elevation Model data. For example, a dataset for China, which shows the land's height at a 30-meter detail level, was put together in 2015 using this Copernicus data. This particular dataset was created by taking the larger Copernicus product, which the European Space Agency put out in 2022, and then fitting it together and cutting it down to cover the specific area. So, you can see, there are different versions and updates over time, which, you know, ties into the idea of "chron" – how things change and get refined through the years.

What About the Details of DEMs and Chron?

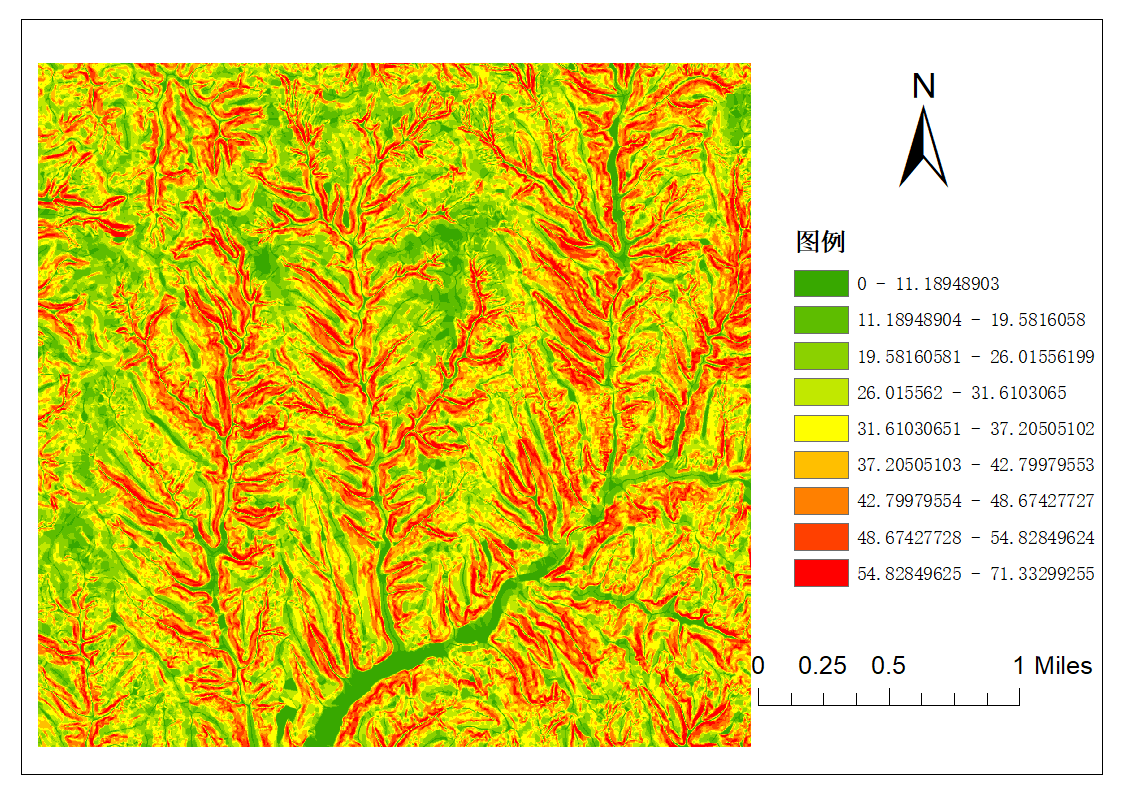

When we look at these digital elevation models, the DEMs, there are some specific things that help us understand how detailed and useful they are. One of the key things to think about is their "resolution." This tells us how small of a feature on the ground the model can actually pick up. For instance, some of these DEMs are described as having a "30-meter accuracy." This means that the smallest thing you can really make out on the map is about thirty meters across. It gives you a pretty good idea of the ground's shape at that level of detail, which is, you know, quite useful for many purposes.

The ASTER GDEM, which we talked about earlier, is a good example of a 30-meter resolution digital elevation model. It's a very commonly used dataset because it provides a good balance of detail and coverage. The fact that it's available at this specific resolution means that if you're looking at, say, a large area like a province, you'll get a consistent level of detail across the whole region. It's like having a consistent zoom level on a map, which is, honestly, pretty helpful when you're trying to compare different parts of the land. So, these details about resolution are, like, really important for anyone working with this kind of data.

Looking at the 30m Resolution for DEMs and Chron

Let's focus a bit more on what that "30-meter resolution" actually means for DEMs. When a digital elevation model is said to have a 30-meter resolution, it's telling you about the size of the smallest square on the map that has its own unique elevation value. Think of it like a grid laid over the land, where each square in that grid is 30 meters by 30 meters. Every one of those squares gets assigned a single height number. This means that any features smaller than 30 meters, like a small ditch or a tiny bump, might not show up individually, but rather get averaged into the height of that 30-meter square.

For example, the ASTER GDEM 30m resolution digital elevation data is a specific kind of DEM that provides this level of detail. It's a standard type of data that many people use because it offers a good balance between how much data you need to store and how much detail you get. You know, it's a practical choice for many mapping projects. And when we consider "chron" here, it's interesting to note that these resolutions often stay consistent across different versions of the same product, making it easier to compare changes in the land over time without having to worry about different levels of detail.

What About Other Meanings of DEM and Chron?

Now, let's switch gears a bit and talk about a completely different set of meanings for "DEM" and "chron," the ones that show up in the world of international trade and shipping. Here, "DEM" actually stands for "Demurrage Charges." These are fees that a shipping company might charge when a ship or its cargo stays at a port for longer than the time that was agreed upon in the contract. It's, basically, a penalty for delays in loading or unloading goods. Imagine you've rented a truck to move your stuff, and you keep it for an extra day; you'd likely pay an extra fee for that extra time. Demurrage is kind of like that, but on a much larger scale with big ships and their valuable cargo.

Then there's "DET," which often goes hand-in-hand with demurrage. "DET" stands for "Detention Charge." This is also a fee related to delays, but it's usually about the shipping container itself, rather than the ship. If you keep a container for too long outside the port, past the free time allowed, you might get hit with a detention charge. So, "chron" in this context refers to "Detention Charge." These charges are, you know, very important in trade contracts because they help make sure that ships and containers keep moving, which is vital for global commerce. They're all about making sure things happen on time, or else there's a cost involved.

Understanding DEM and Chron in Trade

When we talk about charter party agreements in international trade, which are basically contracts for renting a ship, these "Demurrage Charges" (DEM) come up quite a bit. A court, for example, might look at these demurrage fees and see them as something that happens because the person renting the ship couldn't finish loading or unloading the goods within the time that was set out in the contract. It's, essentially, a way to make up for the ship being held up when it should be moving. These kinds of fees are a very real part of doing business when you're moving goods across the seas.

So, when you see "DEM" and "chron" in a trade document, you know, they're not talking about maps of the earth's surface at all. Instead, they're talking about the financial side of keeping things on schedule in shipping. The "chron" part, referring to detention charges, specifically addresses the containers. It's about how long you hold onto the equipment. These terms are put into contracts to protect everyone involved and to encourage efficient operations. It's a pretty practical way to handle potential delays, ensuring that if things don't go as planned, there's a clear understanding of the financial consequences.

How Do We Use DEMs and Chron?

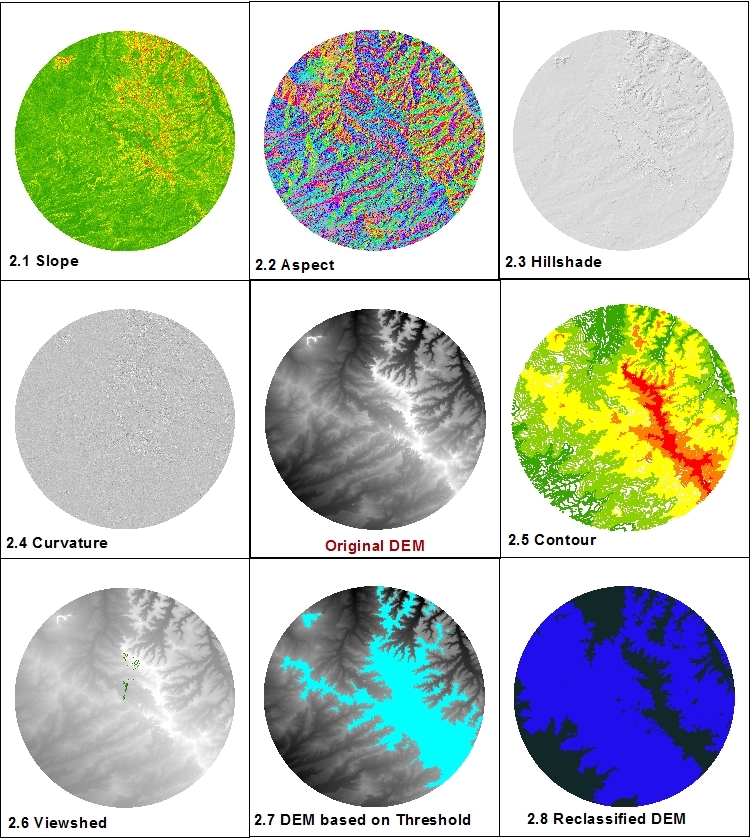

Now, let's circle back to the digital elevation models, the DEMs, and talk about what people actually do with them. One really cool use is creating 3D effects. If you want to see what a piece of land looks like in three dimensions, like a miniature model you can spin around, you can use software for that. For instance, a program called ArcScene is often used to make these kinds of 3D views. It takes the flat elevation data and turns it into something you can really visualize, giving you a better feel for the terrain. It’s, like, pretty neat to see the hills and valleys pop out from the screen.

Beyond just making things look 3D, DEMs are also super useful for other mapping tasks. People can use them to create contour lines, which are those lines on a map that connect points of the same height. These lines help you understand the slope of the land – how steep or flat it is. There are even tutorials out there, like ones for the Aowei Interactive Map software, that show you how to get DEM data, bring it into the program, and then draw those contour lines. So, if you're ever wondering how to figure out the best path up a mountain, a DEM can be a really helpful tool. It's, honestly, all about giving us a clearer picture of our physical surroundings.

Putting DEMs to Work and Chron

One of the more advanced ways people use DEMs involves something called "interferometry." This is a method where you first create what's called an "interferogram." It's a kind of image that shows how much the ground has moved or changed. Once you have that, you can use it to complete other analyses related to elevation. For example, NASA's SRTM, which stands for Shuttle Radar Topography Mission, used interferometry to gather elevation data of the Earth's surface. This mission was designed to collect information about the land's shape, and it did so by bouncing radar signals off the ground and measuring the time it took for them to return.

This process of collecting topographic data, which is all about the shape and features of the land, helps us build a very detailed picture of our planet. The information gathered from these kinds of missions then gets turned into those digital elevation models we've been talking about. It's, you know, a pretty involved process, but the result is incredibly valuable for all sorts of things, from planning construction to understanding natural disasters. And when we consider "chron" here, it's about the timing of these missions and how the data collected at specific points in time helps us track changes on the Earth's surface over different periods.

In summary, we've looked at "DEM" in two very different ways: as Digital Elevation Models, which are like detailed maps showing the height of the land, and as Demurrage Charges, which are fees in shipping. We also touched on "chron," which in the shipping world refers to Detention Charges. We saw that DEMs, the elevation models, come from sources like Maxar, NASA, and the European Space Agency, with examples like ASTER GDEM and Copernicus DEM. These models come in different versions and resolutions, like the 30-meter detail. On the other hand, Demurrage and Detention charges are about managing time in trade, making sure ships and containers move efficiently. We also explored how elevation DEMs are used for creating 3D views and contour maps, and how they're built using methods like stereo photography and interferometry. It's clear that while the words might sound similar, their meanings are quite distinct depending on whether you're looking at the Earth's surface or the flow of international trade.

What is a Digital Elevation Model (DEM)? Where can I download DEM Data

DEM实验|基本地形因子的提取和DEM的可视化 - Weltㅤ - 博客园

DEM Analysis – The many uses and derivatives of a Digital Elevation